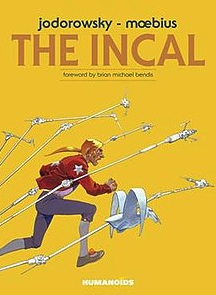

1. The Incal

Written by Alejandro Jodorowsky, the famous Chilean-French filmmaker whose attempt at a Dune film has gone down in history as one of the greatest missed opportunities by film production companies of all time, The Incal is one of the highest-rated sci-fi comic book series you can find online. The story unfolds in Jodorowsky’s original universe, the “Metabarons Universe,” an avant-garde mixture of fantasy and futuristic speculation which actually includes some of the themes, imagery, and even artwork that had been prepared for Jodorowsky’s dune.

The Incal is the story of a private eye named John DiFool who finds himself caught up in a conflict of galactic scale after coming into possession of an incredible artifact known as the “incal.” While his life had been nothing of galactic importance up to that point, his backstory is certainly colorful. Explored in the second installment of the Incal series, Before Incal, we find out that John DiFool is as much a product of his environment as he is a shaper of it. He is a quintessential anti-hero, struggling with his vices and his own cowardice in a confusing and strange universe.

Much like Jodorowsky’s other works, Incal bears the markings of the absurd and the surreal. Unlike some avant-garde storylines, it does not engage in over self-indulgence, instead making exploration into the nature of humanity and how we tend to build upward without addressing the problems in our foundations.

As would be fitting for a man who hoped to employ surrealist painter Salvador Dali in an acting roll for Dune, the Metabarons Universe is rife with twisted religions and vague, organic mysticism that rises from the troubles and the mysteries of the everyday.

2. Ghost in the Shell

Ghost in the Shell, a manga series both written and illustrated by esteemed artist Masamune Shirow, is enjoying a healthy influx of new fans, despite having an original run that started in 1989. The Ghost in the Shell original manga has inspired a number of interpretations across multiple mediums, the most famous by far being the 1995 animation of the same name. The manga is recognized for its incredible art, thought-provoking storyline, and its iconic lead character Major Motoko Kusanagi. While the film and the subsequent anime series were what brought most western readers to the series, the comic has maintained popularity for decades after its original run.

Ghost in the Shell takes place in a fictional Japanese megapolis called Niihama, which features hyper-industrialized corporate blocks overrun with the signs of human life that would have otherwise been displaced; slapshod residences, neon lights, and an underbelly of crime have sprung up far beneath the high-rises of the elite. The urban grime present in all iterations of Shirow’s work may have even been inspired by the styles found in both Cyberpunk classics Blade Runner and AKIRA (see item #3,) both of which released seven years prior to Ghost in the Shell and are largely considered to be leading influences on the sparse genre now recognized as Cyberpunk.

Major Kusanagi, often simply referred to as “the Major,” is intimidating, aloof, and seemingly unstoppable to those who do not know her, no doubt empowered by her countless cybernetic enhancements. To her most trusted teammates, however, she shows some vulnerability, including insights into her relationship with her two girlfriends (relationships between cyborgs, especially homosexual relationships, are strictly illegal in Niihama.)

The Major is a devoted investigator and clandestine agent who works for Public Security Section 9, a heavily-armed, urban counterterrorism and intelligence unit with considerable access to the inside of Japanese politics. It is through her work with Section 9 that she encounters the most difficult case of all, one that will haunt her, and many readers, for years.

It is the seemingly unsolvable case of the Puppeteer that brings the lion’s share of depth to the Major’s story, forcing readers to confront the meaning of personhood, self-determination, and civil rights alongside the Major herself.

3. AKIRA

AKIRA is another foundational sci-fi work that has inspired countless other challenging and emotionally gripping sci-fi stories throughout the years since its creation. AKIRA was born in 1982, brought to life by Katsuhiro Otomo, who created both the manga and the feature film that followed it. Otomo was honored with an Eisner Award in 2012, becoming the fourth manga artist to ever be granted the award. In addition to AKIRA, Otomo is recognized for creating Steamboy and Metropolis, two critically acclaimed animated films. AKIRA was one of the first manga series to ever be translated into English in full, published by a Marvel Comics subsidiary in the United States.

AKIRA is a story about both the power and the cruelty that can exist within us. Set in a post-World War III Japan, AKIRA tells the story of a small gang of disenchanted teens who live among the urban decay of Neo-Tokyo, a city that rose from the ashes of Toyko, which was utterly destroyed in World War III.

Neo-Tokyo is a city in strife, with regular protests and riots both from religious groups who believe that doomsday is night and with anti-government groups who believe the Neo-Tokyo authorities are hiding things from the people. In the streets of this city, many youths belong to street gangs, having slipped through the widening cracks in society. It is no surprise that most of the characters of this story are orphans, given the widespread destruction that occurred shortly before their birth.

AKIRA is considered to be emblematic of the disenchantment many Japanese artists explored and expressed during the 1980s, as many creators who were coming into their own artistically had, like the characters, grown up in a recovering society. AKIRA handles issues of loneliness, loss of faith in society, betrayal, and identity with a rarely-found grace, delivered through the vehicle of awe-inspiring cyberpunk flair.

4. Bitch Planet

One of only two comics on this list that are actively publishing new issues (as of the creation of this article,) Bitch Planet, written by Kelly Sue DeConnick and illustrated by Valentine De Landro, is a reimagining of 60s and 70s exploitation films set in women’s prisons. To quote the writer directly, Bitch Planet is “born of a deep and abiding love for exploitation and women in prison movies of the ‘60s and ‘70s.”

DeConnick, a nominee for the Best Writer Eisner Award, was previously best known for her work on Pretty Deadly, an indie comic universe of her own creation well-recognized for its deft genre-bending and fantastic storyline. De Landro also bears an impressive resume, having done artwork for the Marvel Knights and X-Factors series.

(Source: “Kelly Sue DeConnick tackles exploitation tropes in ‘Bitch Planet'”. Hero Complex. January 24, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2015.)

Bitch Planet features a diverse cast of women from all over the world, exploring their life-history, arrests, and prison drama through the lens of an over-the-top, pulpy incarnation of feminist artistry. The main cast of characters finds themselves in the interstellar clink, far away from any semblance of normal society. In the world of Bitch Planet, women who fall out of society’s good graces find themselves locked up on a remote penal colony where violence is the norm, and the daily agenda is anyone’s guess.

The bleak setting brings about critiques of religion and politics from a feminist angle, exploring how society treats women who are different, the way society treats women, and the many ways women survive in an unequal world.

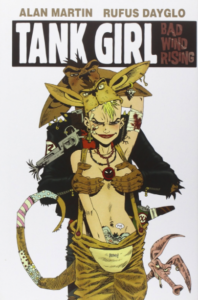

5. Tank Girl

Differing greatly from the common expectations for works of sci-fi, Tank Girl is widely considered to be a punk-science-fiction mashup that brings the audience for a ride as wild as the lead character.

Tank Girl was written by Alan Martin and Illustrated by Jamie Hewlett (of Gorillaz fame) and released in 1988. Tank Girl has had various iterations and installments, including an upcoming new series known as The Wonderful World of Tank Girl, which is set to release mid-2018.

Tank Girl is the story of Rebecca Buck, who more frequently goes by Tank Girl because she drives a tank which also serves as her mobile home in the grungy and chaotic world of future Australia. Tank Girl’s friends and companions include a collection of talking stuffed animals, a kangaroo-mutant (named Booga, who is also her boyfriend,) and, of course, Boat Girl, Sub Girl, and Jet Girl.

The storyline of Tank Girl is intentionally absurdist, loose-cannon, and wild, delighting in chaos in both in its writing and in its visual design. It is a rare stream of consciousness piece that still falls within the science-fiction genre, while doing everything it can to subvert, parody, and corrupt the common tropes and clichés present in both comics and science-fiction at large.